© Calum E. Douglas, 27th July 2021.

The bombing of Germany continues to elicit a great deal of controversy. The views range from “All is fair in love and war, what did Germany expect?” through to: “The Allies lost the moral high-ground by intentionally obliterating civilian areas, the means are as important as the end”. This website will not explore the moral component, but will instead look at exploring the sucess of what has become known as “The Strategic Oil Campaign”, which began in approximately March 1944 (the official date is May, but serious attacks were already in progress) and peaked in November 1944 (although it carried on until the very end of the war). That said, the Oil Campaign certainly resulted in dramatic reduction in civilian casualties relative to attacks on targets in, or on the periphery of cities like Dresden.

The first question for the planners of any bombing offensive, is to decide what the goal of it should be. Obviously the overall goal is to end the war, but to do so, the bombers must still be given a specific set of targets. There are of course a large set of targets which one might propose.

- Electricity generation

- Food

- Fuel, lubricating oils and fuel-oils (for ships)

- Political & decision making hotspots (Parliaments, command centres etc*)

- Mechanical manufacturing facilities

- Mining

- Transportation

- Chemical industries

- Academic and Industrial Research centres

- Military testing facilities

- Direct attacks on the armed forces (airfields, harbors, ships, tanks, soldiers barracks)

* There is evidence that most of the major players (usually) shied away from wiping out or assassinating enemy high command personalities, despite the obvious attractions of doing so. Probably they rightly worried that if the attack was not 100% successful on the first try, that reprisals might be made, in which case it would be their necks on the line. During interrogation by General Carl Spaatz, Göring responded to the question on why Allied commands (such as Eisenhower`s in Africa at one point) were not directly attacked, he responded to Spaatz “We did not like to attack headquarters anyway. We thought that might be a mutual understanding.” See:

Interrogation of Reich Marshall Hermann Göring (pg 15)

RITTER SCHULE, AUGSBURG

1700 to 1900 Hours

10 May 1945

This lengthy list is far from exhaustive, and with a conventionally armed military, removing all of these targets is clearly impossible. So some form of prioritising is required. Factors important in forming such a list include:

- Duration, how quickly do we need the impact to be observed in the enemy`s operations ?

- Post war considerations, after it ends, we may have to occupy the country until a stable (friendly) system of government is installed. If we wipe out means of food production by poisoning the water and the earth, this will make occupation very difficult and even more expensive.

- What are the acceptable losses before home political support diminishes ?

Electricity would seem an obvious choice, however, there were a phenomenal number of plants involved in electricity generation in wartime Germany (around a hundred major facilities). So this is in fact, very difficult to wipe out. Food cannot be wiped out economically, but supporting industries like the fertiliser plants (which rely principally on Nitrogen) can be. Manufacturing plants are surprisingly difficult to eliminate, even plants which “appear” to be destroyed may in fact have machines which are in most cases still workable, which can simply be distributed or even moved underground. Transportation is hard to eliminate without complete air superiority, which facilitates low level operations against trails and roads. Research and testing centres can be wiped out, but the effect of this may not have any noticeable impact on the enemies operations for years, and direct attacks on the military can merely be replaced if the enemy still has energy, materials and factories.

[Please open the images below in a new window or download them or the detail is impossible to see]

In the end, the lynchpin proved to be the petrochemical industry. It is at the very centre of the “web” of industry and warfare. Thus instead of having to wipe out nearly a hundred electrical stations (which would have resulted in such a dilution of bombing, that they would have been repaired reasonably quickly, for the most part) – the oil industry could be eliminated by wiping out around twenty facilities, and in fact, even just six would be enough to stop the Luftwaffe, as only a very few plants made high performance fuels for aircraft.

The Allies knew rather a lot about most of the German manufacturing facilities, as, somewhat awkwardly, both British and American engineers, chemists and firms had played a significant role in both information exchange, and indeed construction of German fuels infrastructure in pre-war times.

Ethyl corporation, and also the British fuels specialist F.R. Banks were two of the guilty parties in this unfortunate conflict of interest. Banks finally admitted in a confidential interview on the 7th November 1973 to the British Air Historical Branch – that he was also a spy for British Air Intelligence, reporting directly to Archie Boyle on German activities in the 30`s – something many had already strongly suspected. Banks had done everything up to, and including dining with Herman Göring.

This of course, did not harm our ability to make accurate intelligence assessments of German wartime fuel and oil production efforts.

This War Cabinet report, was the final report of 1943 before the air offensive markedly changed in character in early 1944. Two serious problems had beset the daylight raids in 1943, firstly the idea that the heavy armament and high altitudes used by the American daylight formations would be sufficient protection with a moderate escort force – proved to be little more than wishful thinking. The Luftwaffe was in a fairly denuded state by 1943, but even so, they still managed to inflict very severe losses on several occasions. Secondly the two fighters doing most of the escorting, were the P-38 Lightning, and P-47 Thunderbolt. Both proved to be deficient in certain respects for this specific task, despite being very capable aircraft overall. The P-38 had done very well in the Pacific theatre, where temperatures were much higher, combat altitudes slightly lower, and the technical capabilities of the opposing fighters of an overall lower standard than those of the Luftwaffe. In Europe, the aircraft proved difficult to operate and disappointing in relative performance. The cabin heaters proved woefully inadequate, and after very long high altitude missions, some pilots became so cold that they were unable to climb out of the P-38 when they landed in England after the mission. In addition, the higher performance of German fighters meant that the P-38 had to stretch itself, and in high speed dives, catastrophic structural failures could occur which were traced to fundamental aerodynamic difficulties with the overall airframe layout. As a result the P-38 was eventually instructed to assume a defensive posture in escorting duties, in other words, not to pursue German fighters into extended dogfights over Germany, and to stick to warding them off the bombers. Some of these difficulties were at least partially rectified in the late model P-38J, but by that point it was too little too late in Europe.

The P-47 had several outstanding capabilities, it was extremely heavily armed, had excellent high altitude level speed, very high performance in dives and much more agile that it ought to have been considering its size. However, although it could cope with German single engine fighters far better than the P-38 could, it was often at the edge of its performance limit in such engagements to keep parity. Sufficient, but it did not have a large margin of superiority over a well flown German fighter at all altitudes. Therefore it too, was not quite as able as the planners wished to go out and seek out the Luftwaffe and aggressively destroy it, and the fact it consumed nearly twice the fuel per hour of the Mustang, which was about to enter service over Europe in January 1944 – made developing drop tanks for it, a very challenging affair, (this is another story worthy of its own article, but a drop tank for a high altitude fighter is a very complicated affair, and the largest “ferry tanks” the P-47 had been using were not pressurised, which made them totally unsuited for use at high altitudes, as the fuel began to boil).

Some legends from the Second World War quickly fade away once the original documents are subjected to scrutiny (there is no evidence what-so-ever that any German ever called the P-38 the “fork tailed devil”, and although the Germans certainly always respected the Spitfire, their conferences were not full of worried discussions about it, they actually spent most of the later war years panicking about the Mosquito, and how bad German radar was compared to the “primitive” British equipment, which was anything but). A study of the documents reveals however, that the reputation of the Mustang, is entirely deserved.

Erhard Milch at one German Air Ministry meeting on German fighter development was asked about developing the Messerschmitt to counter the Mustang. He dejectedly responded:

Göring <engages in a long rant about how the Luftwaffe cant even reach Glasgow>

Galland: “In a Mustang! Thats how you can do it.” …

Erhard Milch: “The Mustang is in another class altogether…”

See MILCH microfilm, RLM Conference 23rd May 1944, 11am, Berlin.

The combat statistics are astounding, by the time the Mustang formed just 15% of the Allied escort waves, it was responsible for almost HALF the total kills. Faced with statistics like these, Allied planners were left with little choice, it was clearly an aircraft which was ideally suited to the particular requirements of escorting over Europe, and despite the many qualities of the P-38 and P-47, the Mustang in this particular role, was just statistically producing dramatically better results than any other available aircraft.

The emergence of the Mustang fitted in perfectly with the about-turn in tactical doctrines the Americans proposed in late 1943. Instead of sticking with the bombers, fighters were to fly high, above the bombers, and ahead. They would then dive on the incoming German interceptors and aggressively wipe them out before the bombers arrived, and if necessary, follow them home and destroy them.

This could have been done by the P-47 and P-38 alone on all but the most remote targets in Germany where the slightly superior range of the P-51 came into the fore, but the cost in losses would have been considerably higher. After a few months, the writing was on the wall, and the P-38 and P-47 were officially phased out of the European theatre. By late 1944, only a tiny proportion of the American escorts were anything other than Mustangs.

The last point I`ll make on the P-51, is the controversy as to how much of its performance was due to the laminar flow wing. It has been suggested that it didn’t really work in practise, and that the clean lines of the Mustang, and the excellent radiator system were the cause. In fact, all three were required, but as far as the efficacy of the wing goes. The Germans tested it and had this to say:

This diversion into how the bombing campaign was facilitated by improved escorts now complete, lets get back to oil…

Without it the enemy cannot fight, move, or repair his forces and infrastructure, this industry is also intimately tied to Nitrogen and Ammonia production, without which the manufacture of modern propellants for ammunition and fertilisers for food, is impossible (Ammonia is needed to make Nitric Acid, which is required for high explosives). This of course, depends on the stocks the enemy has, and if they can be destroyed too. Fortunately for the Allies, Britain had extraordinarily good intelligence on German fuel stock and production levels (essentially by adding up all known imports since the 30`s, and estimating the production possibilities of all the known production plants in Germany, with the aid of industry experts from I.C.I and Shell – together with estimates on supply from friendly sources – eg Romania)

Despite this great success, of the 1944 campaign, which utterly ground all German military activity to a halt, in fact the same operation had been attempted by the RAF during the Battle of Britain. A total of 344 bombing raids were conducted by the RAF against German oil and fuel targets between May 1940 and March 1941 (AIR-8/1019 pg 51). However the forces available were woefully incapable of either the required accuracy or delivering sufficient tonnage to destroy the targets. Although some minor successes were achieved on a handful of missions, this early effort achieved no significant military goals. Perhaps unwisely, this early oil campaign, was suspended in early 1941, as at the time, given its lack of success, it was seen as a higher priority to put effort into anti-invasion measures, as a renewed attempt by Hitler to invade the British Isles was anticipated.

(AIR-8/1019 pg 51)

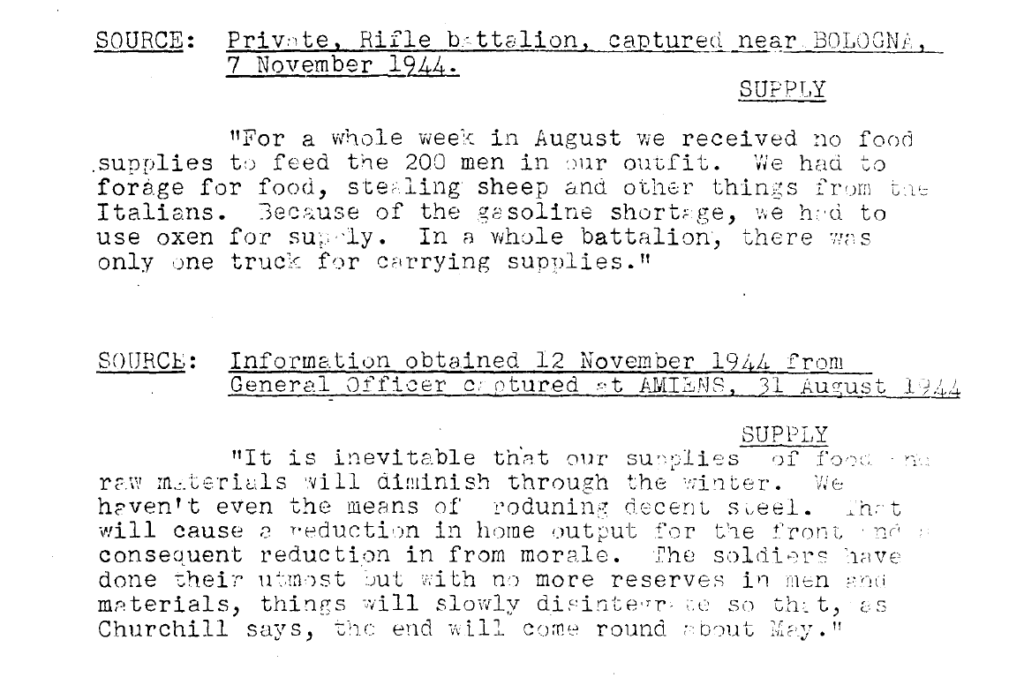

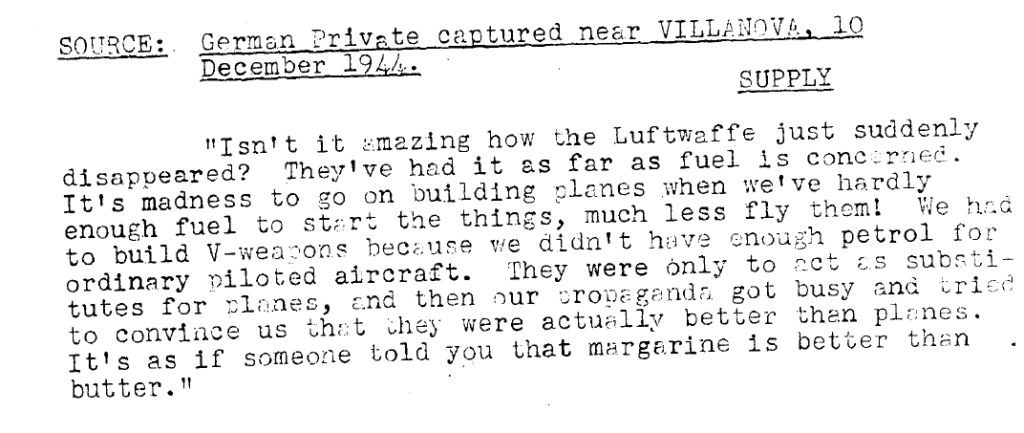

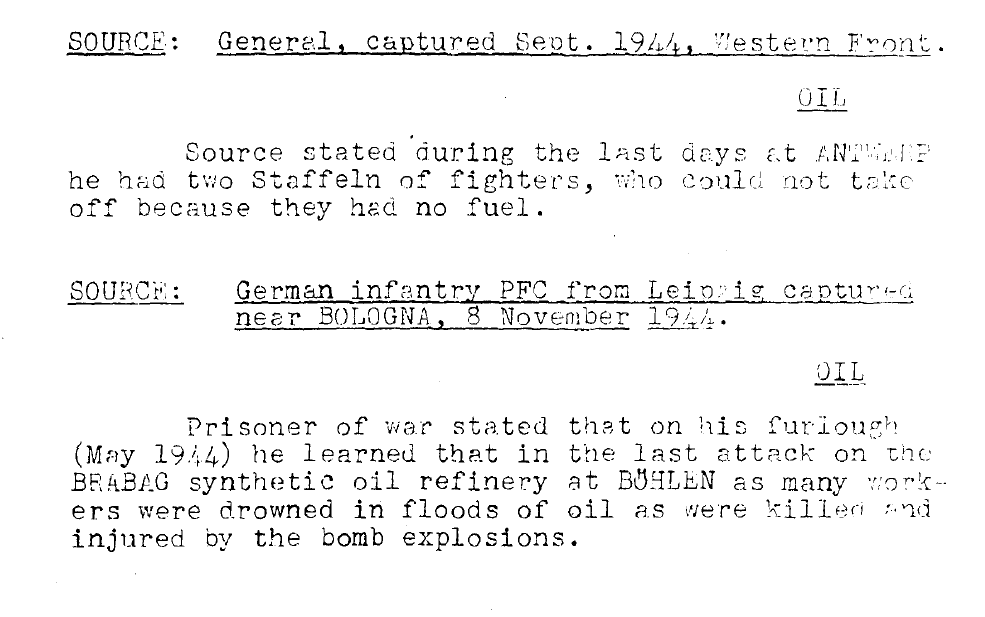

would have attempted to amplify the importance of it. So to check this, we need to ask see what the Germans thought about it. This would of course depend on which German you ask, the soldiers would probably tell you that the worst thing about the Allied air force was constant ground attacks and strafing, the aircraft factory manager would tell you the worst thing was his factory being bombed. So the only really sensible thing to do is find out the views of the top bureaucrats and leaders, who, although not necessarily trustworthy, are at least not tied in their viewpoint to one specific niche of the war effort.

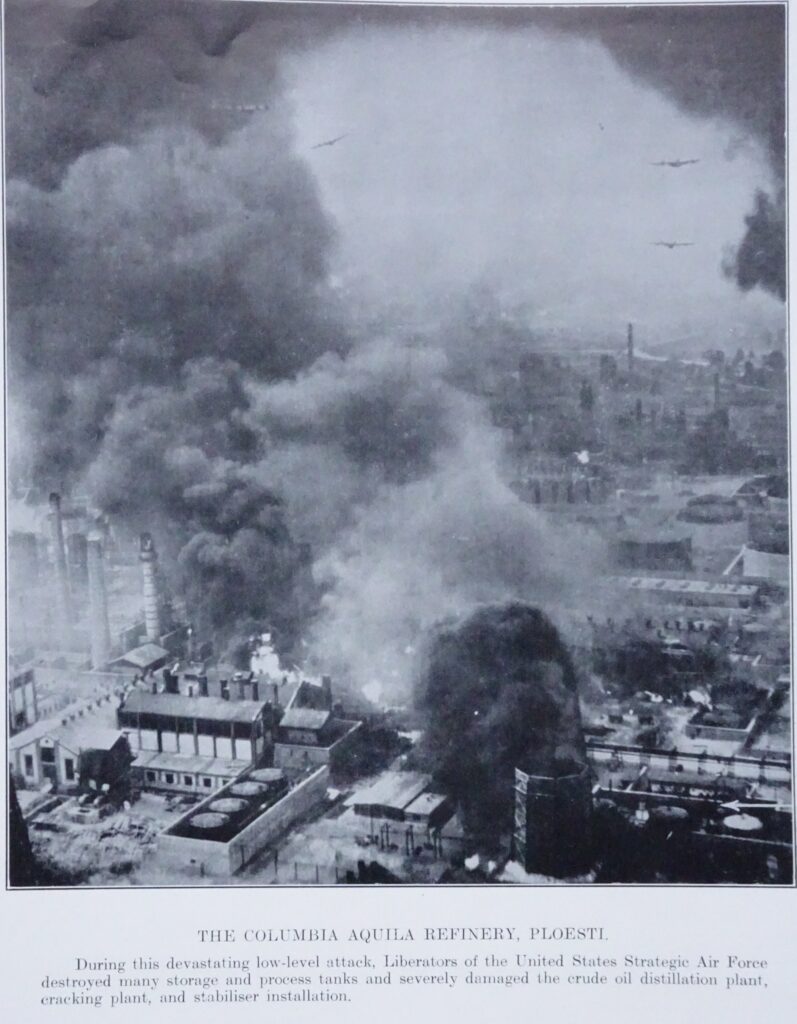

“The hydrogenation plants of the Reich and Rumanian refineries in Ploesti were vigorously

Albert Speer, talking at the Fuhrer Conference of 2nd June 1944 – TNA, FO-1078/71 — “Führer Conferences 1942-1945 Translated”

attacked. All help must be given to get the works going again as soon as possible … the

hydrogenation plants have to fulfil the most important task among all those existing at

the present time within the Reich. Their proper functioning will be practically decisive for

the war, I hope everyone will realise what it means.”

There can be no doubt, that “I hope everyone will realise what it means“, was Speer telling Hitler in a slightly tactfully disguised, but nevertheless straightforward way, that if the plants are put out of action, it meant the end of the war for Germany.

Even outside of the realm of “air”, because Germany was so reliant on fuel from coal, bombing these plants also paralysed the Kriegsmarine, as Dönitz himself noted in this post-war interrogation.

By the May 1944, the attacks on the German petrochemical plants had also begun to have a serious impact on German production of Nitrogen. Without which fertiliser and propellants could not be manufactured. (See MILCH Microfilm, Volume 55, Frames 2233ff – Stenographic Records of “Central Planning Conference” – 18th May 1944.)

The image below provides a good guideline not just to the drop in production, but presented as a loss, compared to what the projected production plans actually were. Which is probably the most important metric.

Actually wiping out oil and fuel production was still surprisingly difficult however, although bombing an oil plant sounds like it ought to be nearly impossible to get wrong, unless certain items like the high-pressure pumps were hit, most of the other infrastructure could be (and was) repaired a lot faster than the Allies hoped.

The trick was not to bomb it, but to bomb it several times, in succession, only then were the repair efforts ground down to such a degree than production essentially stopped. This meant that you had to concentrate bombing on just a very small number of industries, as even the Allied bombing force could not simply wipe out ALL the German industry. Usually about three repeat raids in quick succession was enough to put a plant out of action for months, if however the high pressure pumps were hit, almost instant closure of the plant on a permanent basis could be achieved.

By the end of the campaign, there so so little fuel that both pilot training, and testing of German aircraft engines had been reduced to a pathetic duration. This meant that the aircraft being sent aloft were flown by green pilots, far less capable than a “green” allied pilot – and in addition the already fragile German engines were often falling far short of their intended performance and were horribly unreliable. All but the best aces stood no chance, they were annihilated.

There is also interesting evidence that the lack of conventional high performance fuels impacted the planning for Jet fighter production. Jet fuel, was by comparison, very low grade and simple to produce relative to that needed for piston engine air superiority fighters.

To conclude, whilst it is true that vast Allied efforts also took place against all sorts of Germany industrial and military targets throughout WW2, all of which obviously degraded the German ability to fight – the only sub-set of these targets which could, on their own have stopped the war, was the Oil Campaign. Electricity was too distributed to ever put out of action, but oil was very concentrated in a few high value sites, and without it, even the repair crews would have ceased being able to work, food production and effective munitions production collapsed – and every branch of the German military was virtually immobilised.

In addition to what went right, even the best campaign makes glaring errors, so what were they?

Aside from the obvious error, of ending the campaign early, and not restarting it until after D-Day, the worst error is actually admitted to in the American report often quoted here. The only insurmoutable obstacle preventing Britain from attacking the German petrochemical industry early on, in larger numbers and in daylight (thus circumventing the problem of lack of bombing prescision) was the Luftwaffe. So, if you can FIRST stop the Luftwaffe operating, you can then eliminate the German fuel industry almost at your leisure (Flak of course would always be a problem, but Germany did not develop the proximity fuse in time for wartime use, so German Flak was in fact, markedly less dangerous than it could have been).

So, how do you stop the Luftwaffe ? What sets apart aero engines needed for the fighters who intercept bombers, is very high performance fuel, which also (at the time) meant fuel with very high Tetraethyl-Lead content (about 0.12% by volume). Where did the Germans get Tetraethyl-Lead from ? Well, they had only two plants, one at Gapel-Döberitz, and one in Frose – not only that, but to use fuels high in Tetraethyl-Lead, without it ruining the sparking plugs (the lead slowly desposited on the spark plug heads, and eventually shorted out the plugs, stopping the engine) – the fuel also had to have Ethylene-Dibromide added, which reacted to the lead during combustion, and lowered its vapourisation temperature, thus, it was burned off the spark plugs and carried out the exhaust pipe instead. There was only ONE Dibromide plant in all of Germany, near Hamburg. The total failure to eliminate these three plants (or indeed, even just the Dibromide plant) was a very serious tactical mistake, as it meant that instead of three plants, the bombers had to eliminate six to ten plants to prevent Germany supplying interceptor fighters with fuel. There are presently no good explanations as to why this occured, and only highly speculative remarks noting the investment of American firms in these plants, and attempting to attribute that to their reluctance to eliminate them. The author contacted the German writer on this point, who says he was told about a document proving it, but that he had no copy. Pending further research then, the riddle to why this aspect of an otherwise sucessful campaign was ignored, remains unknown. Incidentally F. R. Banks claims to have told the Targetting Committe very directly of quote:

“The Bombing Committe was always somewhat of a puzzle to us at Ethyl corp…we saw them a number of times during the war…and we told them of their [the TEL plants] extreme importance towards aviation fuel quality yet they were never singled out and bombed”.

F. R. Banks, confidential interview at AHB, November 1973, page 6.

It is mystifying to why his advice was never heeded, especially considering his intimate connections to British Intelligence, and his very high reputation in industry as a consulting expert.

In hindsight, being reasonable with the information the Allies had at the time, the very late stage at which these plants were eliminated is understandable. They did not quite appreciate early on exactly how much Germany was relying on Hydrogenation (fuel and oil from coal) from plants inside Germany (the Allies over-estimated the oil they were getting from ‘Roumania’ and also over-estimated the total stocks Germany had, which may partly explain this).

Using what I`ll call un-reasonable hindsight, it can be argued that the war could have been shortened by perhaps a year, if an all-out bombing effort had been made, exclusively on the ten most critical Hydrogenation plants in Germany. The very effective nature of the 4000lb “cookie” bombs on these plants were noted by American post-war investigators (who counted all the craters and estimated the damage made by each bomb type), suggests that in early 1943, it would have been conceivable for Mosquito bombers to have carried out precision raids against many of these targets (Mosquitos started dropping the very largest and most effective bombs at least as early as 23rd February 1944, by 692 Squadron, see AIR-27/2216/2, 692 Squadron Record Book Feb 1944). Indeed many at the RAF had been actively asking why they had a heavy bomber force at all, once the effectiveness of the Mosquito became apparent – but that is another story !